|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Winter, Italian, 1564 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

In the years when I was between ages 4 and 6 my mother went through a period of serious illness that required her to make frequent visits to her doctor. As she had no one that she felt she could trust to leave me with during her visits, I went with her.

While she was with the doctor I was on my own in the waiting room and, while waiting, would peruse the magazines that were available. In those days it was mostly Life, Time and Look, with the occasional Saturday Evening Post (based on my visual memories of their format). There may have been other magazines too but, since I couldn’t read yet, I can’t be sure of their identity.

One day, in one of the magazines, I remember seeing reproductions of some paintings that both fascinated and repelled me. They still do. These are the notorious “composite portrait” paintings of Giuseppe Arcimboldo.

One day, in one of the magazines, I remember seeing reproductions of some paintings that both fascinated and repelled me. They still do. These are the notorious “composite portrait” paintings of Giuseppe Arcimboldo.

Early Work

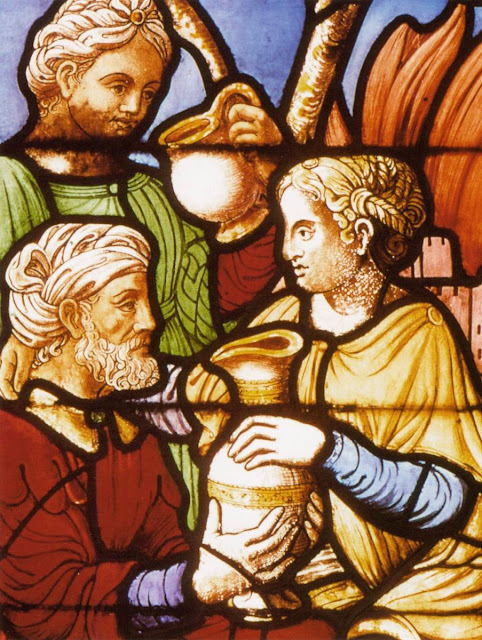

Giuseppe Arcimboldo was the son of the Lombard (north Italian) Renaissance painter, Biagio Arcimboldo. He was presumably born sometime in 1526 or 1527, probably in Milan. In his youth he worked with his father, most notably on designs for stained glass windows in the cathedral of Milan. |

| Biagio and Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Detail from Old Testament Scenes Window Italian, 1549 Milan, Cathedral |

He also seems to have worked in collaboration with other artists on various decorative projects in and around Milan during the 1540s and 1550s. 1

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Zacharias Naming His Son From Scenes from the Life of Saint John the Baptist Italian, 1545 Milan, San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Martyrdom of Saint John the Baptist From Scenes from the Life of Saint John the Baptist Italian, 1545 Milan, San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Death of the Virgin Tapestry Italian, 1558 Como, Cathedral |

In Milan, Arcimboldo could have become familiar with some of the works of Leonardo da Vinci, who had worked in the area at the beginning of the century. Leonardo’s famous Last Supper is in Milan and some of his other work, such as drawings, including his studies of grotesque heads, was also there at the time. Milan was also the home of some of Leonardo’s pupils and assistants, notably Francesco Melzi, Bernardino Luini and Giovanni Ambrogio Figino. 2

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Grotesque Heads Italian, c. 1494 Windsor, Royal Collection Trust |

The mood of painting in these middle decades of the sixteenth century was what is now called Mannerism. 3 The art of the Mannerist period delighted in various kinds of visual extravagances, such as distortions of proportion, complex compositions (with figures often irrelevant to the supposed subject matter being given prominent place), grotesques and visual jokes. It was a sophisticated and deliberately “in” style of art, highly suited for an aristocratic and learned audience, but not well suited for straightforward didactic purposes. One could say, in fact, that in Mannerist art the complexity of the composition and elegance of execution took precedence over content and meaning.

Move to the North

In 1562 Giuseppe moved north of the Alps to offer his services to the King of the Romans (eventually also Holy Roman Emperor), Maximilian II. His move from Milan may have been precipitated by the episcopate of Cardinal (later Saint) Charles Borromeo. Cardinal Borromeo preferred artists who were able to focus their production on a more straightforward and serious presentation of the truths of the faith. In this way he anticipated the aims of what became known as Counter-Reformation art or Tridentine art (named after the reforming Council of Trent, which met in northern Italy from 1545 - 1563). At the imperial court Arcimboldo could hope to obtain work from the kind of sophisticated audience that had supported the Mannerist style in mid-century Italy.

Initially, he painted portraits of the imperial family and court. He also worked as a designer for the kinds of courtly activities that were common in late 16th-century Europe: pageants, tournaments, etc.

|

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Archduchess Anna, Daughter of Emperor Maximilian II Italian, c. 1563 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Archduchess Magdalena, Daughter of Emperor Maximilian II Italian, c. 1563 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Maximilian II, His Wife Maria of Spain and Three of Their Eight Children Italian, 1563 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Costume Drawing of a Knight Italian, c. 1585 Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Costume Drawing of a Woman Bearing a Torch Italian, c. 1585 Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi |

|

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Sketch for a Sleigh Italian, 1585 Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Self-Portrait Italian, c. 1571-1578 Prague, National Gallery |

Composite Heads

Beginning in the 1560s he also began the series of composite heads that fascinated me as a child and continue to fascinate me as an adult.The composite heads are human forms that are composed of flowers, fruits and vegetables or sometimes of other items.

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Fruit Basket Italian, c. 1590 Private Collection |

The Four Seasons

The best known is the series of The Four Seasons, of which several partial sets exist. |

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Summer Italian, c. 1560 Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek |

|

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Winter Italian, c. 1560 Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Alte Pinakothek |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Summer Italian, c. 1563 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Autumn Italian, 1572 Denver, Art Museum |

There is, however, one complete set, which is at the Louvre.

In the Louvre Four Seasons, Spring is made up of flowers and spring plants; Summer is composed of grains, fruits and vegetables (among them grapes, melons and eggplant). Autumn is made from fruits and grains, while Winter shows bare branches, ivy and those stored up sources of vitamin C, lemons.

In Spring teeth are actually lilies of the valley, while peas represent them in Summer. In Autumn a pear becomes a nose, while in Winter mushrooms become lips.

|

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Spring Italian, c. 1573 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Summer Italian, c. 1573 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Autumn Italian, c. 1573 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

|

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Winter Italian, ca. 1573 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

The Elements

He also did a series of heads of the classical four elements: earth, air, fire, water. Two of the Elements are in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

Fire is a head composed of flames, flammable items and items associated with different forms of fire, such as candles, lamps, flint and parts of guns and cannons. Burning coals form the hair.

|

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Fire Italian, 1566 Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum |

Water, who appears, from the pearl earring and necklace, to be a female, is composed of aquatic elements: fish, crustaceans, amphibians, coral, even a tiny seal. 4

|

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Water Italian, 1566 Viena Kunsthistorisiches Museum |

The first of these is Earth. This head is made up of various animals, both predator and prey, all positioned to create the features of a head, including half of the head of an elephant, which creates the ear and side of the cheek, while a fox creates the cheek, even as it snarls at the hare, which substitutes for the nose.

Air is a bearded character, composed of the bodies of birds and birds nests. The goatee beard is formed by the tail of a pheasant, whose head is being inspected by a rooster with a plumy blackish tail. The nose is the head of a turkey and the brow is formed by the body of a duck. The hair is made up of the heads and beaks of multiple small birds. A fanning peacock creates a kind of ruff where the neck should be.

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Air Italian, 1566 Private Collection |

The great detail in these works reflects the detailed studies of animals and birds which Arcimboldo made during his years in Prague. Some of these works can be seen in a manuscript dating from 1575 which is held in the Austrian National Library in Vienna.

|

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Study of a Lesser Kestrel and Flowers Italian, c. 1575 Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek |

|

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Study of a Stag and Violets Italian, c. 1575 Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek |

Composite "Portraits"

The composite heads are sometimes “portraits” of actual individuals. For example, the well-known Vertumnus is a portrait of the Emperor Rudolf II (son of Maximilian II).

|

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Vertumnus Italian, c. 1590 Skokloster (Sweden), Skokloster Castle |

Similarly, the painting known as The Waiter is made up of barrels, jugs, serving implements (primarily ones for serving drink) and the keys to the wine cellar.

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, The Waiter Italian, 1574 Private Collection |

And some are both visual jokes and optical illusions, as for instance the painting titled, The Cook. In that painting we see a platter of roasted meats in the process of being uncovered. But, when it is turned upside down, it becomes a face and the platter becomes a hat.

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldo, The Cook Italian, 1570 Stockholm, National Museum |

Similarly with the painting known as the Vegetable Gardener. When the painting is turned upside down, the gardener's "hat" becomes a bowl full of vegetables.

Final Years

In his final years Arcimboldo painted a head called The Four Seasons in One Head, which may be a self-portrait. In it the flowers of spring, the grains and fruits of summer and autumn and the dead branches of winter all combine.

| |

|

These heads combine a keen, almost scientific, observation of natural elements, vegetable and animal, and of man-made items such as cannons, candles and books, with a playful and ingenious sense of design. Some have seen them as the result of mental illness, but they are more probably expressions of the taste for oddity and the grotesque that can be seen in much of late 16th-century art, especially of the Mannerist art that was associated with the secular courts of the time (as opposed to art intended for the decoration of churches).

|

| Bernard Palissy, Platter French, c. 1580 Paris, Musée du Louvre |

One need only look at the “rustic” pottery of Bernard Palissy in Paris, with its casts of creepy crawlies, and at the grotesque doorways of the house built by the brothers Taddeo and Federico Zuccaro on Via Gregoriana in Rome to see this mood expressed in the minor arts and in architecture.

|

| Palazzo Zuccari, Doorway Italian, 1592 Rome, Via Gregoriana 28 |

Much of this work was regarded by patrons as clever and interesting. Emperor Rudolf II clearly felt this way about Arcimboldo’s paintings because he placed them in his Kunstkammer in Prague. A Kunstkammer (literally “art room”) was a kind of private museum of odd and curious items and included not only paintings but scientific instruments, natural specimens, clever toys, small statuary, in short, whatever unusual object appealed to the owner. 5 Emperor Rudolf’s Kunstkammer was famous throughout Europe. To be placed there was a great honor for Arcimboldo.

However, tastes in art change and the collection was broken up. It was also the victim of looting over the years and was, therefore, widely dispersed. Arcimboldo’s work virtually disappeared until it was “discovered” early in the 20th century by the Surrealists. They obviously felt an affinity with the precise detailing and odd combinations of the composite heads. Since then Arcimboldo has remained a kind of art historical curiosity.

I think of his work as a fitting subject for Halloween, as it seems to fit easily into the atmosphere of disguise and pranks that prevails in relation to this very old festival, which heralds the approach of winter.

© M. Duffy, 2011, updated 2022

_______________________________________________

1. For information on what is known about Arcimboldo’s early life see:

- Kaufmann, Thomas Da’Costa. Arcimboldo: visual jokes, natural history, and still-life painting, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Arcimboldo : 1526-1593, edited by Sylvia Ferino-Pagden. Milano and New York, Skira, 2007. Catalog of the exhibition held at Musée du Luxembourg, Paris, Sept. 15, 2007-Jan. 13, 2008; and at Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Feb. 12-June 1, 2008.

- Kriegeskorte, Werner. Arcimboldo, Cologne, Taschen, 1987.

2. See #1 above.

3. Shearman, John K. G., Mannerism, New York, Penguin, 1967 is a well-known study of the period.

© M. Duffy, 2011

No comments:

Post a Comment